Mined gold supply still not keeping up with demand

2020 was a mixed bag for gold producers. On the one hand covid-19 forced many to temporarily halt operations, due to government-imposed lockdowns.

Yet last year also saw gold hit a record $2,034 per ounce, due mainly to pandemic-related demand shocks, including a sharp drop in the US dollar; the flight from equities to bonds, which drove yields to record lows, thus supporting investments in gold; and monetary easing across the major central banks, comprising a resumption of quantitative easing (mainly bond buying) designed to drive down interest rates and spur borrowing; and interest rate cuts to near 0%, also carried out to incent businesses and individuals to take out loans, and therefore protect national economies from falling into recession during the once in a century global health crisis

With gold prices rising 22% in 2020, a pertinent question is whether the world can produce enough of the precious metal to meet rising demand — especially considering we are entering what could be a particularly ugly period of inflation.

Rising prices of goods and services (inflation) are generally good for precious metals. Gold is the most proven investment to offer a return greater than inflation, by its rising price, or at least not a loss of purchasing power. Due to an increase in inflation every decade except the 1930’s, the US dollar has lost 90% of its purchasing power since 1950.

Gold, on the other hand, has gone from $35 in 1970 to $1,750 in 2021, a 50X increase!

In this article we are revisiting one of our favorite topics: peak gold.

Peak gold

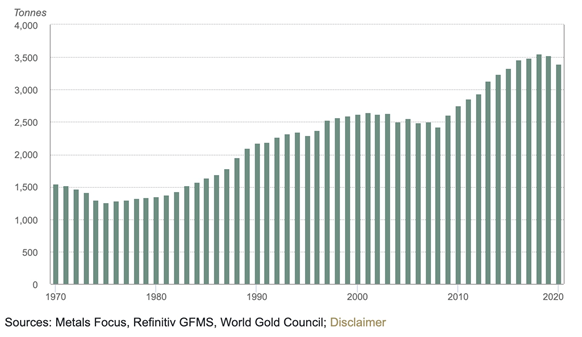

The concept of peak gold should be familiar to most readers, and gold investors. Like peak oil, it refers to the point when gold production is no longer growing, as it has been, by 1.8% a year, for over 100 years. It reaches a peak, then declines.

Peak gold doesn’t necessarily mean gold production will suffer a major fall. However it does mean the mining industry lacks the capacity to ramp up production to meet rising demand; even higher prices would not make that happen, because there aren’t enough mines to tap for more supply.

The idea of peak gold has always been controversial and continues to be. If the amount of reachable, and economic gold resources is finite, presumably gold companies have a shelf life. It means gold mining is a sunset industry that will only see so many more bright orange spheres slipping over the horizon before the last ounce of gold is poured.

If gold is indeed becoming scarcer, prices have only one way to go and that’s up, so long as demand for the precious metal is constant or growing.

In a previous article we proved peak mined gold, and the most recent numbers from the World Gold Council show a continuing slide in mined gold supply compared to gold demand.

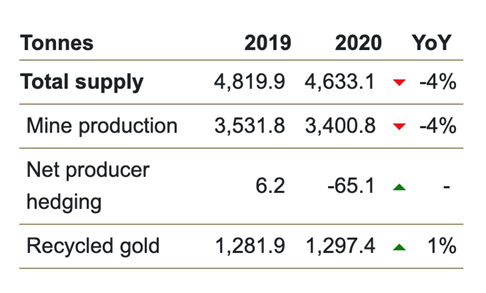

The latest World Gold Council report shows a 4% decline in total gold supply in 2020, compared to 2019. Mine production also slid 4%, to 3,401 tonnes, including just 896t in Q4, a five-year quarterly low. WGC attributes the decreased output to coronavirus disruptions.

Lockdowns occurred in Mexico, where Q2 2020 production was 62% lower, South Africa where production fell 59%, and Peru which saw a 45% drop. In Papua New Guinea mine production was slammed by a suspension at Porgera, the country’s second largest gold operation, following the government’s decision not to renew its mining lease.

In calculating the true picture of gold demand versus supply, we at AOTH don’t count gold jewelry recycling. What we want to know, and all we really care about, is whether the annual mined supply of gold meets annual demand for gold. It doesn’t!

So, in 2020 total gold supply including jewelry recycling reached 4,633 tonnes. Total demand was 3,759t — the first year under 4,000 tonnes since 2009.

No peak gold here, right? Demand is more than satisfied by supply.

But when we strip jewelry recycling from the equation, 1,297t, we get an entirely different result. ie. 3,759 tonnes of demand minus 3,401 tonnes of production leaves a deficit of 358t.

This is significant, because it’s saying even though major gold miners are high-grading their reserves, mining all the best gold and leaving the rest, they still didn’t manage to satisfy global demand for the precious metal, not even close. Only by recycling 1,297 tonnes of gold jewelry could demand be satisfied during 2020.

This is our definition of peak gold. Will the gold mining industry be able to produce, or discover, enough gold that it’s able to meet demand without having to recycle jewelry? If the numbers reflect that, peak gold would be debunked. We’ve been tracking it since 2019, and it hasn’t happened yet.

Lower production, dwindling reserves

The easiest way to increase gold supply is just mine more. That’s difficult to do though, when a mine’s reserves are getting low, and the grades have fallen to the point where only the low-grade material is left to scoop up and process.

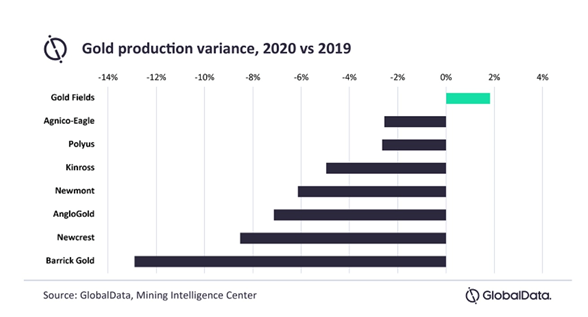

Last year production from the world’s eight largest gold producers fell 6.5%, to 25 million ounces, owing to lower ore grades, asset sales, reduced mill throughput and lower recoveries, according to GlobalData, a UK-based data analytics and consulting company.

Newmont, Barrick and AngloGold suffered the worst production losses, with collective output dropping to 13.7Moz in 2020 form 15Moz in 2019.

In fact, the majors’ gold reserves have been in decline for the past decade. Last September Mining Weekly reported that 16 of the world’s 20 largest gold mining companies, including the three mentioned above plus Kinross Gold, saw their mine lives reduced between 2010 and 2019. Kinross, for example, had just nine years of production left, compared to 24 years in 2010.

Only two of the gold companies analyzed by S&P Global Market Intelligence, Zijin Mining and Fresnillo, had more remaining years of production at the end of the period than at the start.

The cupboard is bare

Gold companies whose assets are depleting often turn to competitors’ portfolios to replace their reserves. In reality mergers and acquisitions (M&A) isn’t really “adding” to the gold supply, it’s just shifting the assets on one company’s balance sheet to another’s.

The more difficult means of creating new gold resources/ reserves is through exploration.

New deposits cost more to discover. This is because they are in far-flung or dangerous locations, in orebodies that are technically very challenging, such as deep underground veins or refractory ore, or so far off the beaten path as to require the building of new infrastructure from scratch, at great expense.

The costs of mining this gold are often too high. Only about one in three advanced-stage gold development projects ever become mines.

In a 2020 report, Wood Mackenzie found that to avoid a perpetual decline in mined gold, the industry must see a rise in the number of gold projects under development that have a good chance of becoming mines.

How many projects? 44, to be exact. Woodmac crunched the numbers and found that by 2025 the industry will need to commission 8Moz of projects, meaning an investment of about $37 billion over the next five years.

Intuitively, that seems virtually impossible – @ nearly nine projects a year.

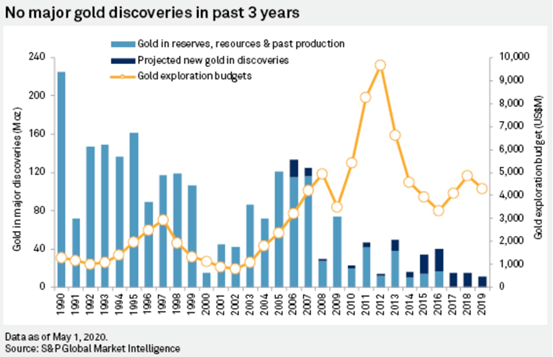

Consider: there have been 278 deposits found between 1990 and 2019 containing 2.194 billion ounces of gold in reserves, resources and past production, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence’s annual analysis of major gold discoveries.

However, within the past three years, there have only been three major gold discoveries, and just 25 in the past decade.

The US-based financial information and analytics firm states the project pipeline is increasingly short of large, high-quality assets needed to replace aging major gold mines.

S&P Global attributes the severe lack of discoveries over the past 10 years to companies focusing on advanced-stage assets rather than searching for new discoveries.

Moreover, the share of gold exploration budgets devoted to grassroots, or greenfield exploration has been cut in half since the 1990s. The problem isn’t confined to majors and mid-tiers, either. According to S&P’s research, juniors [are] increasingly focused on expanding known deposits while producers have increasingly focused on exploration at their existing operations.

Getting granular, we find that of the 278 discoveries within the past quarter century, about half, containing just over a billion ounces, have yet to reach production.

Only 30 have more than 10Moz in reserves and resources, and just nine have grades of 1 gram per tonne or better.

None of the resource announcements made in 2019 met S&P’s major discovery threshold, meaning that all of them have been previously explored. They include Lumina Gold’s 4.2Moz Gran Bestia in Ecuador, a new zone of a deposit discovered in 1999; the 4Moz Chulbatkan deposit found in 1980 and brought to a first resource by N-Mining; and Nova Minerals’ 2.5Moz Estelle project in Alaska, first drilled in 1988.

Some of the assets identified by S&P will enter production over the next few years but others might never be developed, or face a long road to first metal, admits S&P.

The first category includes Barrick’s Goldrush and Zijin Mining’s Buritica; among the second group is Rosia Montana in Romania, which faces fervent opposition; and an example of the third category is the Donlin project in Alaska. NovaGold has been trying to move Donlin forward for decades but it is in the middle of nowhere in southwestern Alaska and lacks infrastructure.

S&P concludes additional grassroots exploration is needed to ensure there are enough projects in the pipeline to replace aging gold mines.

Another mining media list of gold deposits under development is similarly marred. Mining.com’s top 10 gold deposits, released in January, consist mostly of copper-gold porphyries.

Topping the rankings is the Pebble mine in Alaska owned by Northern Dynasty Minerals. The project’s water permit was rejected last November by the US Army Corps of Engineers, putting the future of the 70Moz deposit in considerable doubt.

Four of the 10 have been stalled, along with Newcrest and Harmony Gold’s Wafi-Golpu project, which is facing delays due to an ongoing dispute with the Papua New Guinea government.

That ‘70s show?

Recall Wood Mackenzie saying that by 2025 the industry will need to commission 8Moz of projects, meaning an investment of about $37 billion over the next five years.

This does not take into account the fact that gold demand might go up, and it probably will.

Consider what we know about the current gold market.

The blistering speed of economic recovery in the US — economists are predicting annual GDP growth of 6.5%, versus a 2020 contraction of 3.5% — is stoking fears of inflation.

In a recent interview with ’60 Minutes’, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said the Fed won’t raise interest rates based on short-term jumps in inflation readings.

However there is reason for concern that in fact, inflation is rising faster than expected and that could present a real dilemma for the Fed: allow prices of goods and services to rise, beyond what is comfortable for the middle and lower classes who typically bear the brunt of inflation; or hike interest rates during an economic recovery that is by no means on a strong footing — with unemployment continuing to be higher than before the pandemic (9.7 million in March 2021 compared to 5.7 million in February 2020) despite resumption of economic activity, and covid-19 still raging throughout the land.

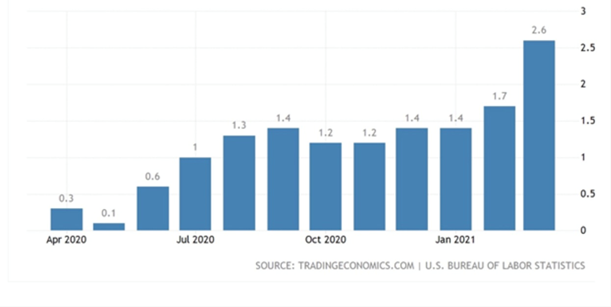

The consumer price index (CPI) jumped 0.6% in March, led by higher oil prices, and the 12-month rate of inflation rose to 2.6% in March from 1.7% in February, as the bar graph below shows.

The rise in CPI is even more startling considering that 12 months ago inflation was close to 0%. The year over year gain is the highest since August 2018, and the month over month increase is the most since June 2009.

The actual inflation rate is already above the Fed’s 2% target, and we’re not talking about core inflation which strips out food and energy “because they’re too volatile” which is ridiculous.

Anyone who buys groceries and gas is seeing their purchasing power eroded on a daily basis due to inflation, and this inflation is usually not counted in official government statistics.

The last big bout of inflation the US experienced was in the 1970s. During the first quarter of 1973, consumer prices skyrocketed by nearly 30%, farm prices climbed 52% (red meat prices shot up 90%) and the cost of home heating nearly doubled.

Today’s fiscal stimulus, which includes the trillions already spent on covid-19 relief and more to come with Joe Biden’s proposed $2 trillion infrastructure bill, and plans for education and health care, dwarfs anything even considered in the 1970s. Moreover, there is a palpable excitement that Americans will finally be able to discard the shackles of covid and spend the money they saved last year and the wages they’re starting to earn again. So demand is likely to soar.

Regarding interest rate hikes — the common cure for inflation — the Fed is constrained by a runaway national debt, currently sitting at a mind-boggling $28 trillion.

Sooner or later people must realize that with all the money-printing that goes along with the tax and spend Biden administration, combined with runaway growth due to economies coming out of the pandemic, we are going to be struck by a major run of inflation.

Over time, inflation erodes the purchasing power of fiat currencies and eventually they become worthless.

Will it become like the ‘70s? Hopefully not, but who knows? How can you protect yourself just in case?

A dollar today is worth 99 cents tomorrow and 98 cents the day after; history proves it. That’s what happens when you save in paper money not backed by gold.

Since 1972 gold has gone from $35 to $1,750. That’s the power of precious metals. In my opinion the coming inflation and soaring global debt levels all but guarantee another gold run is on its way.

![]()