Dr Sixtus Mulenga: Dreaming of the future

This mining stalwart’s long journey to discover new minerals is an inspiration to every Zambian

How many people would leave a prestigious job, their home, their family, and the lifestyle that they’d worked incredibly hard to build for a tent in rural Zambia, in pursuit of a dream? That’s what Dr Sixtus Mulenga did.

His dream was to make a new mineral discovery in an unexplored part of Zambia.

Fourteen years later, having parted with most of his hard-earned savings, he’s still living in a tent in rural Luapula. But, having discovered substantial manganese deposits, Dr Mulenga is now the owner of Zambia’s first wholly and privately-owned large-scale, indigenous mining company: Musamu Resources Limited. This is his story.

***

Dr Mulenga has been a trailblazer since the outset of his mining career. He was among the very first Zambians to qualify as a geologist back in the 1970s, when he attended North London Polytechnic, now University of North London. Next came a Master’s and then a PhD at Imperial College London’s Royal School of Mines. He returned to Zambia and became the first Zambian mining geologist to be employed at Bancroft – today’s Konkola Copper Mine (KCM) – which was then operated by Anglo American.

Dr Mulenga rose to Chief Geologist at the mine, which had been renamed as KCM, under the ownership of Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines Limited (ZCCM Ltd). “I had to work hard to move up the ladder. It took focus, dedication and consistent performance,” he said. In time, he became Consulting Hydro Geologist for the ZCCM Ltd group. “So, for five years – from 1995 until 2000 – I was the ‘top guy’.” During this same period, he also served as a member of the ZCCM Ltd Technical Team on the privatisation of ZCCM Ltd.

After privatisation – and with Anglo American running KCM – he spent a few years as Vice President of the company’s Safety, Health, Environment and Quality (SHEQ) portfolio. “That was one of the highlights of my career,” says Dr Mulenga. “I learned a lot about sustainable economic development during that time, which really strengthened my zeal for what was a relatively young concept in the mining world.”

It was during this chapter of his career that Dr Mulenga began providing mining consultancy and technical advisory services to the World Bank. “The experience exposed me to the global mining industry, and I started to see sustainable development in action. That’s when I knew I needed to go out into the world and put these concepts into practice for myself one day.”

“I started to see sustainable development in action. That’s when I knew I needed to go out into the world and put these concepts into practice for myself one day.”

The next frontier

It was January 2009 when Dr Mulenga began the long and very risky process of starting his own self-funded mineral exploration project. He pored over geological maps and scoured geophysical data for clues, focusing on parts of the country which showed high potential for mineralisation but had not been explored. He settled on an area in the north of the country, in Luapula Province – home to several large geological basins, where part of the Central African Mineral Belt rolls over Zambia’s borders – and decided on a 1000-square-kilometre swathe of land within what’s called the Lufilian Arc, in Luapula’s Chipili District. “I had a sense this spot was rich in minerals, but I went with an open mind. I wasn’t looking for manganese in particular – I was looking for everything.”

Dr Mulenga took the coordinates of the area, applied for a mining exploration licence, left his home in Kalulushi, and drove north.

“I went with an open mind. I wasn’t looking for manganese in particular – I was looking for everything.”

“I come from Northern Province, but we speak broadly the same language as people in Luapula Province. I went to the Chief and introduced myself. I told her: ‘I’ve got this licence that covers your area, and I’d like to set up a camp.’ I needed three things: water, a road and, if possible, a cellular network. And I needed them to be as close to the centre of my licence as possible.”

This was, in some sense, a ‘make or break’ moment. Buy-in from traditional leaders is key for an exploration plan to progress from vision to reality.

“‘Welcome, my son,’ she said to me. ‘I’m so happy that you’ve come here because if you find minerals, my area will be developed.’ She gave me her guide and asked him to take me to a nearby village, Chulu Luongu.” Together with a small team, Dr Mulenga began building a camp about two kilometres from that same village – and that’s where he’s been living ever since.

“That first night in the camp was special. I slept under a big tree. I felt I was free with nature.”

Solving the puzzle

Dr Mulenga had one exploration geologist working with him. “After that, I started building a team, and I paid them from my own pocket. I had about seven technicians and I recruited around 100 of the local villagers. There was a lot of physical work to do: cutting clearings in the bush to collect soil samples, for example.”

For the next three years, Dr Mulenga busily went about soil sampling, mapping, and surveying the geophysics of the area, using whatever ground level and airborne data he could find. “Mineral exploration is like a puzzle,” he said. “You have an idea in your mind and when you’re doing your mapping, looking at the geological structures, and doing your sampling and your chemistry, you’re looking for a pattern. We call that an ‘anomaly’.” Soon enough, he had found one.

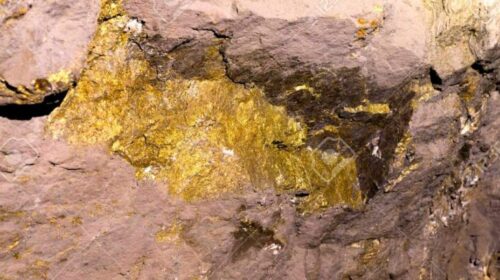

One day in July 2012, as he approached his sixtieth birthday, Dr Mulenga experienced one of the most memorable moments in his long and illustrious mining career. Suddenly, at the bottom of a trench – about two metres deep – he saw it: manganese. What does manganese ore look like? “Black,” he smiled.

“That was a really, really exciting day!” said Dr Mulenga. “The next big moment came a couple of years later when I drilled the first hole,” he explained, eyes bright. “It was just after midnight. At that time, we were drilling into the night because, once you start, you don’t want to stop. I was too eager! I had to see what was there… And out of that hole came manganese.”

He phoned his wife in the small hours and told her what he’d found. “Oh, thank God!” she replied, more than three years after her husband had embarked on what was ultimately an extremely costly endeavour, with no guarantee of finding any minerals at all.

“I couldn’t sleep, he said. “My brain was so happy! For 24 hours I was wide awake.”

Walking your talk

What came next was “drilling, drilling, and more drilling,” explained Dr Mulenga, as the team explored the size and shape of the deposit. By 2017, Dr Mulenga had hired an environmental consultant to do an environmental impact assessment. Again, an abundance of patience was required, a trait without which Dr Mulenga could never have achieved what he has.

“The environmental impact assessment took three years because it was a greenfield project, so I repeated the assessment for each season. That was another very interesting period because it gave me direct communication with the community. It gave me an opportunity to explain what the project was about, what impact it will have on them, and how it will create employment.”

From day one, he’d encouraged the villagers working for him to look to the future. He presented the two possible outcomes of his exploration project: “Either I am successful and I find minerals, or I fail. I told them they should plan for the latter. If I don’t find anything, for me, it’s just my ego and the money I’ve spent. But they’d have nothing to show for the time they’d spent working for me.” Every one of his long-standing employees took his advice: his technicians built new houses in their hometowns, and around ten of the villagers who’d stayed on built modern, metal-roofed houses in Chulu Luongo village.

From sustainable foundations to growth

With the environmental impact studies approved, in March 2020 Dr Mulenga applied for a mining licence. “The President of Zambia, Mr Hakainde Hichilema, officially opened the mine on 3 November 2022,” he said, smiling widely. “And, all these years, I’ve been funding it – and I’m still funding it. But now I require investment partners to take this project to the next level.”

“All these years, I’ve been funding the project – and I’m still funding it. But now I require investment partners to take this project to the next level.”

The resource in Chipili District has approximately 40 million tonnes of manganese, which will be further quantified during the resource definition phase. “In the location where I’ve started the mine, there is a certified reserve of one million tonnes,” said Dr Mulenga. “The whole idea of building this project is to have a fully-integrated mining business, where we will do mining and value addition. We plan to build our own processing plant and beneficiate the manganese to the stage where we can feed it into the electric car battery-manufacturing value chain.”

Manganese is a critical metal used in two of the world’s most prominent types of rechargeable battery and, as the world moves more decisively towards a green energy transition, demand for manganese is rising each year. But Dr Mulenga has his sights set far higher than battery metals alone. Manganese is also an essential alloy that helps to convert iron into steel. The potential for Zambia to tap into opportunities for value addition are far-reaching, and extend into several sectors. But above all, perhaps, Dr Mulenga wants to lay the groundwork for economic diversification around his new mine. One source of inspiration has been Kalumbila – a mining town that was designed to outlive the mine for which it was established. Dr Mulenga’s mind is brimming with ideas for creating an ecosystem in which mining operations catalyse development in sectors like agro-processing and manufacturing that can sustain themselves beyond the life of mine.

“Looking to the future is an integral part of what I’m doing, and it’s what I believe in. I’ve always felt that mining can do more.”

***

Dr Mulenga dreams big. After all, he founded Zambia’s very first wholly and privately-owned large-scale, indigenous mining company. The name he chose is ‘Musamu Resources’.

“‘Musamu’ means ‘medicine’ and it also means ‘tree’,” explained Dr Mulenga. “But from a philosophical point of view, a musamu signifies growth and development, which speaks to the Green Revolution we’re embarking on. You’ll notice there are two trees in my logo: there’s a bigger tree and a smaller tree. The bigger tree signifies the world. And me? I’m a small tree that’s part of a bigger forest – the forest of global development.”

***

Look out for Part 2 to find out how Dr Mulenga plans to develop a sustainable and diverse economy around Musamu Resource’s manganese mine and processing plant, designed to outlast the operations that brought it to life.

![]()