Mining sector’s failure to seek new copper jeopardizes entire energy transition

Mining company executives’ preference for safe, short-term returns has led to a massive underinvestment in new copper mines and exploration, jeopardizing the metal-intensive energy transition.

The shift toward decarbonization will require vast amounts of copper to extend transmission lines, install new wire in renewable power sources, and electrify existing appliances and cars. Despite this nearly certain demand, the mining industry has spent the past decade moving much of its profits away from finding and developing major new copper projects.

Instead, industry members have favored expanding mines with stronger guarantees of shorter-term shareholder returns and growing dividends and share buybacks. But new copper mines take decades to achieve commercial production, and they come with risks including permitting issues and shifting political landscapes. Meanwhile, new discoveries are frequently of lower grades, making the copper more expensive to extract.

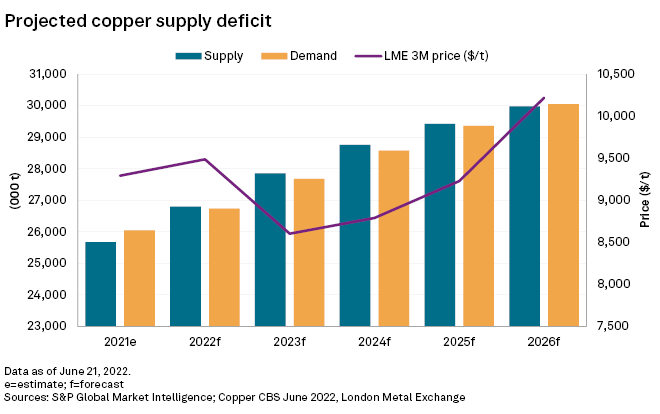

All of these challenges combine to create hurricane-force headwinds for a speedy economic transition toward electrification and renewable power. In the most optimistic scenario in its recent “Future of Copper” report, S&P Global estimates the world will be short 1.6 million tonnes of copper in 2035, with major deficits beginning this decade. In its most pessimistic view, that shortfall expands to 9.9 Mt in 2035.

“The challenge is that if current trends continue … there’s a huge gap,” said Daniel Yergin, vice chair of S&P Global and project chair of the group behind the recent analysis, which projects massive copper deficits emerging in the coming decade. “And even if you put on your roller skates and your jet burner [to realize optimistic supply growth], and everything goes right, there’s still a gap, because it’s enormous. And it’s important to recognize that now, not in 2035.”

Bear market bite

In part, the origins of the coming shortfall lie in the mining industry’s response to economic pressures in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, according to Commodity Insights mining analyst Kevin Murphy. After a frenzied upswing in metals and mining equities that started in the mid-2000s, the sector fell into a protracted bear market for about a half-decade after 2012.

“And then companies were left with this huge debt level for these assets that they were developing,” Murphy said. “That led to this really quite long period of rationalization … where companies opted to reduce what they had in their holdings.”

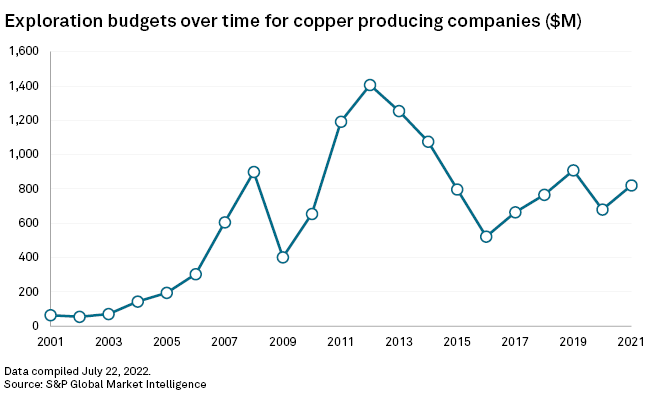

These cutbacks included exploration budgets. After peaking at approximately $1.41 billion in 2012, the exploration budgets of reporting copper-producing companies steadily declined through 2016 to $522.5 million. Exploration budgets rebounded slightly to $820.8 million in 2021, but that was still 41.6% lower than the 2012 high.

The frothy bull market in metals in the early 2010s drove miners to aggressively explore and develop less promising projects in the hopes of capturing high prices. Average discovery costs were less than a cent per pound of copper in the 1970s, surging to over eight cents per pound from 2010 to 2019, according to Richard Schodde, managing director at Minex Consulting.

“The reason why the last decade was almost a lost decade for copper … was the fact that there was a hot market for exploration, which led to inefficient cost inflation,” Schodde said. Many miners also targeted “low quality projects” in a bid to profit from known deposits rather than take risks.

READ MORE: Sign up for our weekly ESG newsletter here, read our latest coverage of environmental, social and governance issues here and listen to our ESG podcast on SoundCloud, Spotify and Apple podcasts.

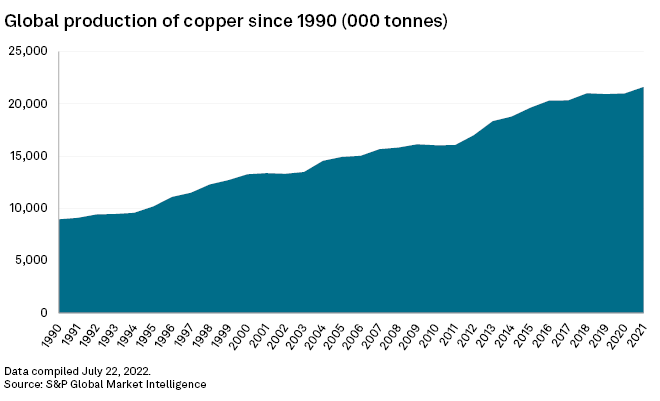

Lackluster exploration spending has yet to stymie copper supply, as the new finds of 20 years ago are now in the production stage. Global production of copper has been on a steady upswing for decades as demand has climbed, including on a per capita basis.

But the pipeline of future projects is thin, and the industry will be unable to meet anticipated demand. Over the next 28 years, total copper demand is set to match cumulative copper consumption since 1900, John Mothersole said during a July 14 call on the “Future of Copper” report. Mothersole is director of nonferrous metals, economics and country risk at S&P Global Market Intelligence.

“Copper mines don’t grow on trees,” Robert Friedland, founder and executive co-chair of Ivanhoe Mines Ltd., said on an Aug. 15 earnings call. “And we’re not going to have clean air or make a meaningful impact on the climate, nor are we going to be able to act on the so-called inflation reduction bill [in the U.S.], without a massive increase in demand for copper metal.”

Regulatory conundrum

Long lead times for mine development will prevent the industry from rapidly making up for lost time. The National Mining Association estimates that it takes seven to 10 years on average to obtain the permits necessary to bring a mine into operation in the U.S. The lead time is even longer starting from the moment of a deposit’s discovery.

“If it actually gets approved and everything goes well, it tends to be in the 20-year time frame,” Murphy said.

This lengthy lead time, combined with volatile copper prices and government policies that may slow development or create political instability, can discourage companies from opening or exploring for new deposits, according to analysts. For example, miners in Chile have warned that a proposed tax increase on copper production by the government could lead to a decline in mining investments, amid a growing political shift to the left in South America, a top copper-producing region.

“There’s always been those sort of challenges, but I can see it becoming sharper,” said Schodde. “As the world gets more interconnected, you can’t hide the impact, or potential impact, of a mining project on a local community.”

In response to those challenges, major mining companies have tried to garner social licenses to operate increasingly large mines, making project development more difficult and time-consuming, Schodde said.

“I think we can say that issues other than economics are becoming increasingly influential to a project’s success,” Vanessa Davidson, CRU Group director of base metals research and strategy, said in a June 13 presentation at the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada conference in Toronto.

As demand for South America’s copper grows, the region’s politics have emerged as a greater drag on industry growth than was the case during the last supercycle, which started in the early 2000s on the back of searing economic growth in China.

“And most [of these] governments have a socialist agenda,” Schodde said. “And to fund those programs which make them popular, they’re going to need money. The easiest targets for them is the mining industry.”

Roadblocks to individual projects can also discourage new investment. Northern Dynasty Minerals Ltd.’s Pebble copper-gold project in Alaska, for example, has faced shifting rulings from the U.S. government every time a new political party came to power in recent years.

Brownfield versus greenfield

To avoid some of these problems, companies may opt to expand existing mines rather than develop new projects. Greenfield exploration brings the lure of a major discovery, yet also comes with massive risks. Finding a meaty new deposit or discovering one in a region where development may go smoothly was never an easy thing and it is has become increasingly tough in recent decades.

“[One] reason that we don’t have an expansion [of supply] commensurate with the demand that will come from the so-called energy transition is very simple: If you’re a mining business, the magnitude of costs and amount of time required … put that business at extraordinary risk. You have to spend billions and billions of dollars to open new mines,” said Mark Mills, senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and faculty fellow at Northwestern University.

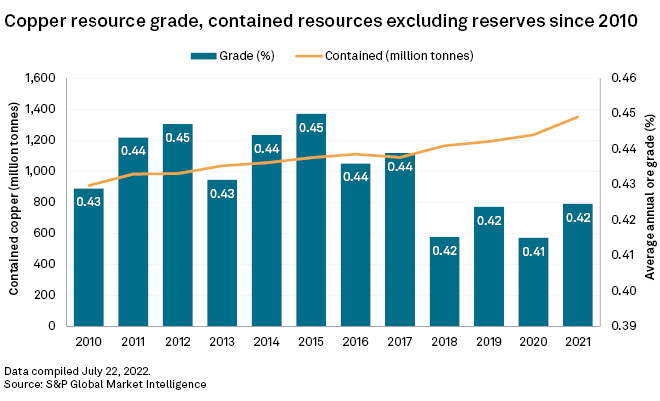

With expansion often comes declining ore grades, increasing the cost of extracting the same amount of copper. Experts expect the copper industry will be able to develop the technological knowledge to efficiently process these lower grades, at least in the near term.

“Ore grade declines are an established, enduring feature of the industry,” said Anthony Lea, president of the International Copper Association. “The industry has always responded … [and] we’re confident that they will continue to respond to that kind of ore grade challenge.”

Powering the energy transition

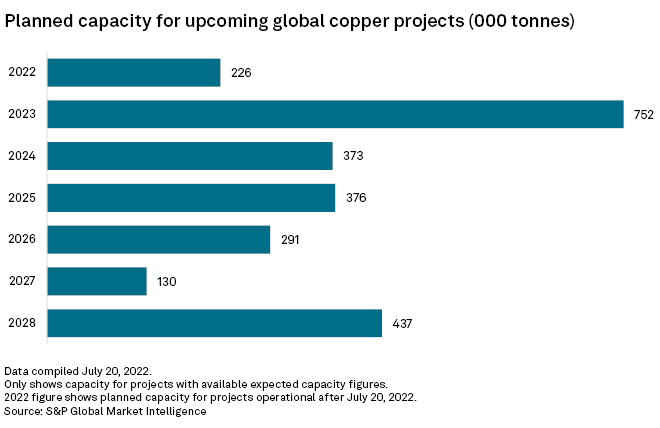

Still, exploration expenditures and planned capacity increases do not reflect the magnitude of projected demand growth for copper, analysts say.

“Even under the high-ambition scenario, the very optimistic scenario, we see large deficits or shortfalls emerging in the market … in the next 10 years,” Mothersole told Commodity Insights. “It’s just staggering.”

If supply is not there, demand destruction may ensue, and things such as electric vehicles and copper wires may not be able to be made at the levels required to hit net-zero targets.

“It means … the energy transition goals would be pushed out further into the future,” Yergin said.

Source: SPGlobal

![]()