Tin must tame its wildness to meet coming demand surge

The world is going to need another 50,000 tonnes of tin per year by 2030 to meet a looming surge in demand, according to the International Tin Association (ITA).

Tin is an often overlooked critical mineral, commonly associated with the humble tin can, even though packaging today accounts for only 12% of global usage. Almost half the tin consumed every year is now used as a solder in circuit boards.

The faster the world moves towards the internet-of-things, the more tin will be needed to glue the expanding metaverse together.

Tin will also benefit from the green energy transition thanks to its use in solar panels and batteries, both lead-acid and lithium-ion.

The additional production required to feed the coming demand boom is a big ask of a sector that currently produces around 380,000 tonnes per year of primary refined metal.

A recent history of extreme price volatility and growing resource nationalism in Indonesia, the world’s largest tin exporter, add to the challenge.

Rollercoaster ride slows … for now

The ITA estimates the tin production sector needs around $1.4 billion of investment to deliver 50,000 tonnes per year more tin by the end of the decade.

It’s a relatively modest amount, equivalent to around one medium-sized copper mine, but investors have in the past been wary of a market prone to extreme swings in price.

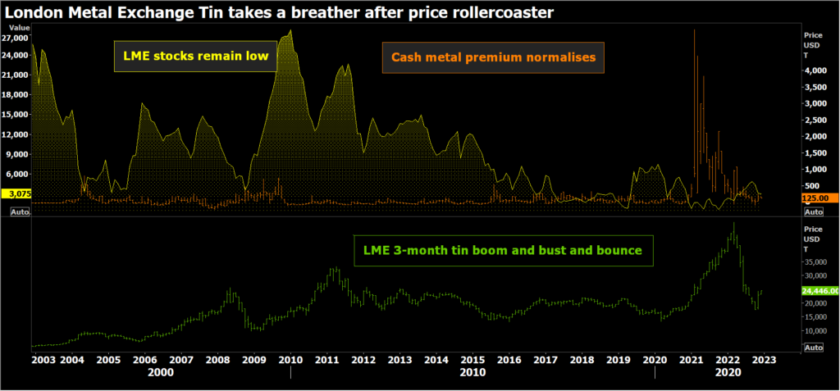

This year has been a particularly wild ride, London Metal Exchange (LME) three-month tin imploding from a record high of $51,000 per tonne in March to a two-year low of $17,350 in November before bouncing to a current $24,430.

Tin’s spin from boom to bust is in part down to covid-19.

Key producers in Asia and South America were hit hard by lockdowns and quarantines, output at the world’s top 10 operators sliding by 13% over 2020 and 2021. Demand simultaneously exploded as locked-down populations splurged on consumer electronics to pass the time.

Both drivers have gone into reverse this year, producers lifting output just as demand for consumer goods abates.

Tin users expect demand to contract by around 0.6% in 2022 after stellar growth of 7.6% last year, according to the ITA’s annual survey.

The shift in fundamentals, however, has been sharply accentuated by speculative flows on both London and Shanghai markets.

Investment fund positioning on the LME swivelled from record long in March to record short in October, equivalent to some 20,000 tonnes of net selling, which is a lot in what is one of the exchange’s less liquid contracts.

Too much rather than too little liquidity is the problem in Shanghai, where volumes and market open interest surged as the price collapsed, suggesting a mass bear attack.

The subsequent recovery rally has generated a lot of churn on the Shanghai Futures Exchange (ShFE) tin contract with volumes hitting a record monthly high of 3.98 million lots in November. But market open interest also remains elevated at 98,474 contracts, implying the bears are largely holding their ground.

Tin moved onto the investment radar in China last year with a step-change in activity on the ShFE contract. Heightened speculative activity in what remains a small physical market comes with the potential for more price turbulence.

Indonesian uncertainty

Indonesia’s talk of banning exports of tin ingot injects significant fundamental uncertainty into the speculative mix.

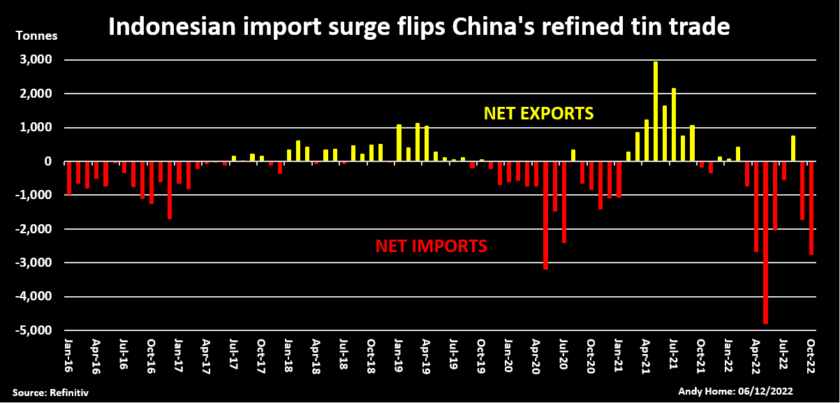

The country exported 75,000 tonnes of refined tin last year with shipments running 8% higher through the first 10 months of this year. It is the world’s biggest supplier outside China.

The government wants to replicate its success in the nickel sector, where a ban on exports of unprocessed ore generated a build-out of value-add processing capacity.

The key difference with tin, however, is that the Indonesian authorities spent much of the last decade tightening export rules such that what leaves the country is already in high-purity refined form.

A move further downstream requires more advanced technology to produce solder or tin chemicals.

State producer PT Timah needs around two years to develop its existing tin chemical facility and longer to secure markets, Alwin Albar, chairman of the Association of Indonesian Tin Exporters, told a parliamentary hearing.

No date for any ban or restrictions has yet been set as the government studies potential time-lines.

But the threat of disruption is already impacting market dynamics with Chinese buyers trying to get ahead of any change in export rules.

China imported 22,600 tonnes of refined tin in the first 10 months of the year with Indonesian metal accounting for 19,000 tonnes. That’s more than China imported from Indonesia over 2020 and 2021 combined.

Higher imports have helped Shanghai stocks rebuild to 4,708 tonnes from a meagre 1,260 at the start of 2022.

But it’s noticeable that LME inventory has started sliding again as Indonesian metal gets diverted to China. After peaking at 5,160 tonnes in September, headline LME tin stocks have fallen to 3,075 tonnes with 535 tonnes awaiting physical load-out.

Desperately seeking stability

New tin projects aren’t viable at a price of $18,000 per tonne. Nor is a significant amount of the artisanal mining that plays a big part in the global supply picture.

But they don’t need a price of $50,000 either. An ideal scenario for new projects would be a stable $25,000-30,000 range, Thomas Bünger, Chief Executive of First Tin, told the ITA’s Investing in Tin seminar.

Most tin producers would probably agree and the market could really do with a breather after the price swings of the last two years.

Unfortunately, the combination of high speculative activity on the Shanghai market and possible disruption to Indonesian exports suggests the current calm may not last long.

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

![]()